MANCHESTER, NH – Joe Whitten, a Manchester native, was working in IT in Boston seven years ago, but looking to start a company that was closer to his heart and also would have an environmental or missional impact.

He got the spark he needed when a friend mentioned that as a teen in California he’d worked for a clothing recycling company, but didn’t see many in New England.

Whitten did some research and decided it was worth a go.

Apparel Impact started small in 2014. Whitten, who grew up on the West Side, went door to door across the city, leaving pamphlets attached to garbage bags, to see if the need existed.

After six months, he determined that people were, indeed, throwing out clothing that they’d rather recycle.

“That became successful to where I knew that people needed to recycle their clothes,” he said.

When he first launched the company, he picked up bags at people’s homes, but quickly changed to drop-off bins. He built the first ones out of wood, vinyl and shingles. “I placed a few in the Manchester area just to see if the idea would work,” he said.

It did. Apparel Impact, based in Bedford, has 22 bins in Manchester, and more than 900 in five states, as well as warehouses in Hooksett and Albany, N.Y., and 22 employees. In 2022, the company’s efforts redirected 9 million pounds of textiles from landfills.

Towns request a bin, and Apparel Impact helps with placement. In smaller towns, that’s usually the transfer station or where their recycling center is. The company services all of its sites weekly, running 12 routes out of the Hooksett and Albany warehouses, with drivers picking up the contents of the bins and bringing them to the warehouses, where the items are sorted and graded.

Nothing that goes into an Apparel Impact bin ends up in a landfill.

“The whole purpose is landfill diversion,” Whitten said.

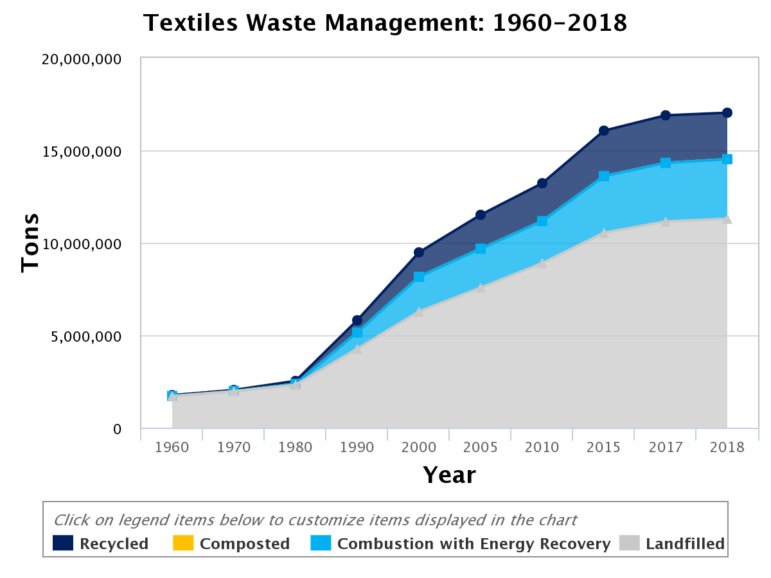

Textile waste made up about 2 percent of what went into landfills 25 years ago in the United States, now it’s 8-10 percent. Much of that is because of “fast fashion,” he said, clothes that are made more cheaply overseas and don’t last the way most clothing once did.

Clothes are heavier than many other products that get tossed away, and get heavier still once they’re dumped at the landfill, potentially soaking up liquids, rain and more. Most municipalities pay a tipping fee for their non-recycled rubbish – a per-ton fee to get it hauled away to a landfill or incinerator.

Whitten said that Apparel Impact hasn’t changed much as it enters its eighth year.

“Since the start of the company we’ve really stayed steady on the goal, which is to provide people the opportunity to recycling their clothing, shoes and accessories rather than throwing them in the trash, it’s just scaled bigger.”

A Little Different

“Apparel Impact is a little different than most of our industry,” Whitten said.

Part of it is the customer service and weekly maintenance of every bin, which he credits with the company’s rapid growth.

Don’t just take his word for it, “Joe does a great job,” said Ken Scheno, Belgrade, Maine’s, transfer station manager as he cleared snow from in front of the town’s one bin. He may have been 160 miles from Apparel Impact’s Bedford office, but it didn’t seem to make a difference as far as the relationship with the company.

Scheno said the driver shows up every week to empty the bin, he’s never had a problem with the service, and the town gets a report every year on how many tons were recycled.

As important as customer service, Whitten said that as a veteran-owned business “We’re focused on supporting veterans and veteran-run organizations.”

Whitten joined the Army at 17 and served as a military policeman and said service to veterans is a major part of the company’s ethos.

Useable clothes, shoes and other items that end up in Apparel Impact bins are disbursed for free to veterans and veterans’ organizations, as well as low-income families and nonprofit organizations.

The company does its own outreach, providing free clothing to up to 4,000 individuals and families a year in New Hampshire and Maine, Whitten said.

The company also has an exclusive partnership with Easter Seals NH, which provides bins to business partners and sponsors, collecting clothing it uses for its own programs.

Apparel Impact also ships clothes and shoes to nonprofits and clothing graders. Clothing that isn’t wearable any more is repurposed by companies into things like insulation and furniture stuffing.

‘A Really Big Problem’

Towns and cities that have Apparel Impact bins see the financial impact on their bottom line – redirecting waste from the local waste stream makes a difference when the per-ton tipping fee is added up. “It’s become a really big problem, not only the environmental aspect, but for towns,” Whitten said.

The Androscoggin Valley Council of Governments, based in Lewiston, Maine, has partnered with Apparel Impact since 2018, helping towns in its three-county western Maine region hook up with the company. The organization awarded Apparel Impact its Environmental Achievement Award in 2019 for what it sees as an innovative and effective way to keep solid waste out of landfills.

“By diverting textiles from the waste stream, it saves valuable landfill space,” said Zach Gosselin, AVCOG environmental and resiliency planner. “It also can save the towns money. It lowers costs for the municipalities by removing that extra tonnage from the waste stream.”

The 20 towns in AVCOG’s region that use Apparel Impact bins diverted 182.3 tons from the waste stream in 2022. The town of Poland, with 5,600 residents, recycled 50.3 tons in 2022, Gosselin said. The second-highest was Rumford, a similar-sized town, which recycled 40.7 tons.

Gosselin said that the program works well for small towns, because the bins “can go anywhere.”

Town and government officials said the fact the bins are emptied and maintained by Apparel Impact makes it easy on municipalities that don’t have a lot of employees, and are stretched thin.

The Kennebec Valley Council of Governments has a program similar to AVCOG’s in its coverage area in central Maine.

Belgrade is one of those towns. Located in the Lakes Region of central Maine, it has a population of 3,000 people in the winter, and twice that in the summer. Scheno, the transfer station manager, said, “We may pay $84-$85 a ton at some points, so [the textile recycling] makes a difference.”

Waterville, Maine, a city of 16,000, recycled 131 tons of textiles through Apparel Impact in 2021, according to its annual report. With a per-ton tipping fee of $70 a ton, it saved the city more than $9,000.

Gosselin said that, aside from the environmental benefit and financial savings, “Apparel Impact does a great job of giving back to those in need, which I think is a great addition on top of what they already do.”

Pickup vs. Dropoff

In many of the northern New England towns and small cities in the areas Apparel Impact operates, it’s the only option for removing textiles from the solid waste stream. Manchester-area residents, though, can also use Helpsy, a New York-based curbside textile recycling company that the city contracted with last year and that also operates in Hooksett, Exeter and other area towns and cities.

Textiles comprise about 6 percent of Manchester’s 38,000 tons of rubbish that ends up in a landfill every year, according to city officials. Estimates are the Helpsy program can divert as much as 129 tons a year from the city’s waste stream.

Helpsy, like Apparel Impact, takes clothes that are no longer wearable, unless they are moldy, wet or have an odor.

But Whiten says curbside textile pickup usually doesn’t work.

He said the model isn’t scalable, not only in less populated areas, but also in cities. It’s why he switched from pickup to drop-off early on. People aren’t constantly throwing out textiles, that means a pickup company is “hiring a full-time driver, or two, to drive around entire city and collect only six bags.”

Textiles left outdoors also are frequently stolen, only to end up in the waste stream, and get wet and moldy fast on a rainy day, he said.

Whitten said his business plan is more sustainable. In fact, in December, Apparel Impact took over Helpsy operations in Vermont, he said, where they will now be doing things what he calls “the Apparel Impact way.”

He said that means “You service the customers weekly, you provide 24/7 phone line service. We’re there every week and they can get in touch with us any time. We’re truly family-owned.”

Laughing, he added, “I mean, we have 930 customers and probably 80 percent of them have my cellphone number.”

To host a bin, find a bin or learn more, go to Apparel Impact.