Story Produced by NH Business Review, a member of

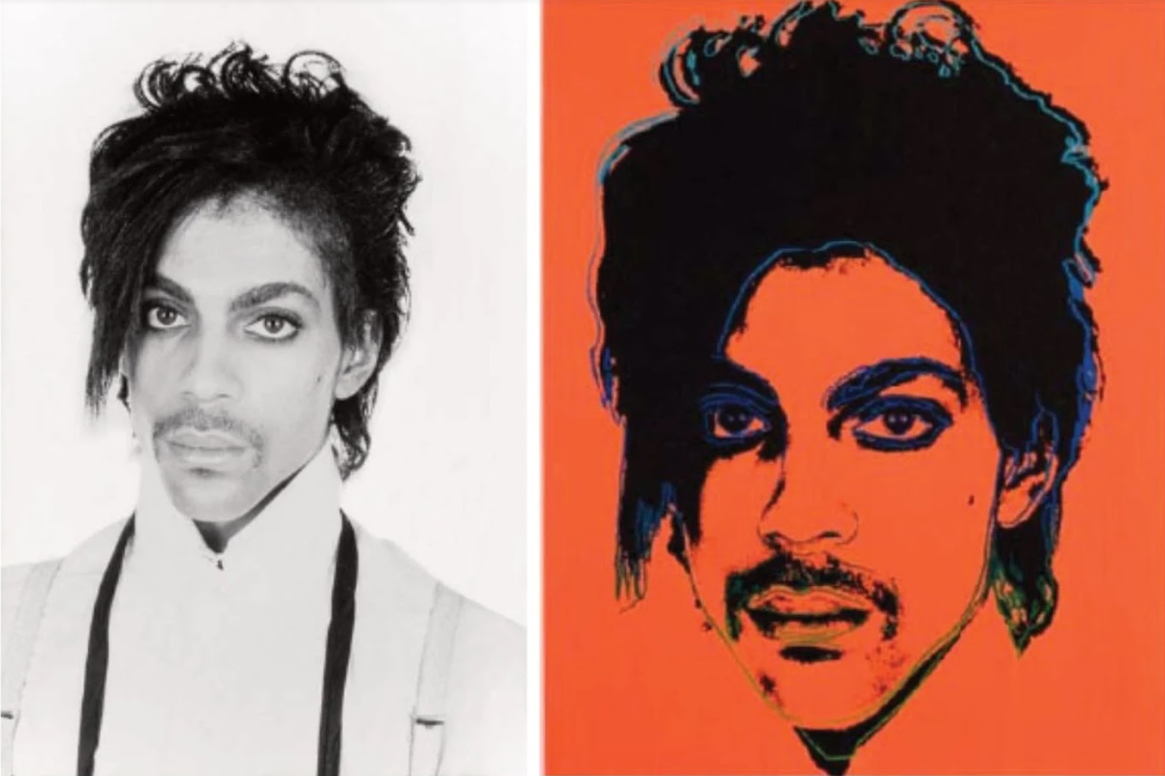

When is art inspired by other art, and when is it simply derivative of the original work? That is the question the U.S. Supreme Court will try to answer in a case involving a series of Andy Warhol silkscreen prints based on a photograph of the artist Prince that a photographer named Lynn Goldsmith took in the 1980s.

The original photographer claims that Warhol infringed her copyrights in the image. The charitable foundation created by Warhol’s estate argues that Warhol made “fair use” of the photograph. The case is known as The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Inc. v. Lynn Goldsmith, and the decision will turn on what makes a work “transformative.”

Fair use is a defense to copyright infringement that courts developed in order to acknowledge that very few ideas are purely original. Most art, science and literature builds on established ideas and concepts. Though universally recognized and now codified in federal law, the fair use defense is in tension with the other purpose of copyright law, which is to encourage creativity by giving authors a monopoly on the intellectual property rights in their creations.

To strike this balance, copyright law considers four factors to determine whether a work qualifies as fair use: (1) the purpose and character of the use of the original work in the secondary work; (2) the nature of the original work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the original work used in the secondary work; and (4) the effect of the secondary work on the potential market for the original work.

Some examples of fair use are straightforward: book reviews, criticism, reporting and parody. Determining what qualifies as fair use becomes more complicated when one moves beyond those categories into art that melds the original work with the secondary one in order to, arguably, create something new. Warhol’s use of a photograph to create silkscreen prints is but one example.

Copyright law attempts to trace the scope of fair use in part by asking whether the purpose and character of the secondary use of the original work is “transformative.” Deciding if a work is transformative requires asking whether the new work adds something new and important to the original.

Until last year, most courts believed that answering that question involved looking at whether the secondary work conveyed a new meaning or message. In the Warhol decision, a federal appeals court disagreed. According to that court, when the works are sufficiently visually similar, the new work is not transformative regardless of whether it transmits a new message. This is in direct conflict with many other courts, which believe that even works making few changes to the original can be transformative if their new message is apparent.

This is the crux of the dispute before the Supreme Court: Can visually similar works be considered fair use if their new message is sufficiently obvious?

Answering this question is complicated by the fact that the case before the Supreme Court involves one of the most celebrated artists in recent memory — Andy Warhol. Warhol was part of the pop art movement that began in the 1950s, which was known for incorporating images from everyday life into works of art. The use of mundane images in artistic works commented upon the visual detritus that had become pervasive with the advent of mass media by recontextualizing it in a different form. Where prior works of art had typically elevated their subject matter, many pop artists presented their subjects with indifference.

The work of artists like Warhol presents a unique challenge to the courts in defining the scope of fair use because the Supreme Court must define the rules for all creative works. For example, the Supreme Court’s most recent fair use decision concerned the extent to which Google’s use of software code that contained portions of code written by another company could be considered fair use. The court concluded that it could because Google had used the code to develop a new platform for the smartphone environment.

It is plain to see that software code and pop art have little in common, but they are both subject to the same fair use doctrine.

What does this mean for the business community? For one, it highlights the broad application of copyright law. Those who create a copyrighted work may be heralded artists, or they may be website designers. The same rules apply to both. Second, the definition of fair use, which is the most common defense to copyright infringement, is ever-changing. What is transformative today may be derivative tomorrow, and one need not be Andy Warhol to find shelter in the defense.

Attorney Ned Sackman, a shareholder at Bernstein Shur, works out of the firm’s Manchester office and specializes in dealer-side automotive and intellectual property matters. Anna Nilles is a summer associate law clerk at the firm.

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.